Aihetta uutisoidaan näyttävästi,

mutta itse asian ytimeen ei liiemmin mennä.

– Koska tuskin koskaan päästään siihen, että itse kukin voisi

elää ja rukoilla tavallaan.

Toisaalta ollaanko pinnallisesti suvaitsevaisia

ajattelematta mihin sekin sitten johtaa.

– Miksi muuten käytetään ulkoisia merkkejä

omasta suuntauksesta?

Meitä sumutetaan!

Näköjään edes lapsia ei säästetä, vaan niistä tehdään aseita vähä-älyisiä aikuisia vastaan! Saatana hyökkää kaikilla aseillaan ja on lähettänyt sakean savuverhon silmillemme!

Katselemme, kuin lumisadetta televisiosta, emmekä huomaa, kuinka kaikilla rintamilla meitä huijataan!

Ilmastokatastrofilla pelotellaan, vaikka kautta aikojen ilmastot ovat vaihdelleet ihmisten vaikutuksesta huolimatta. Nyt on käännetty lasten sormet osoittelemaan vanhempiaan. Opettajatkaan eivät ymmärrä, mitä he pelottelullaan saavat aikaan!

Meidät on saatu kiinnittämään huomiomme epäoleelliseen, emmekä huomaa, että Jeesuksen kertoma lopun aika alkaa olla käsillä! Matt.24

Kaikkea hallitsee hyvävelikerhot, illuminaatti, joka vetelee naruista, kuin sätkynukkeja ohjaillen. Berneri pääpiruna sekoitti taksi, ym. liikenteen. Luulimme, että harmaa talous saa vallan, mutta sekin on saatanan suunnitelma! Pian on pakko lopettaa käteinen raha, että sen liikkeitä voidaan automaattisesti seurata!

Raamattuun on kirjoitettu, että lopunaikana kaikkien pitää ottaa käteen, tai otsaan pedon merkki, ilman sitä kukaan ei voi ostaa, eikä myydä mitään! Siru ihon alle! Sehän on jo tätä päivää! Koirilla!

Ilm.13:16Se pakottaa kaikki, pienet ja suuret, rikkaat ja köyhät, vapaat ja orjat, ottamaan oikeaan käteensä tai otsaansa merkin. 17Kenenkään ei ole lupa ostaa eikä myydä mitään, ellei hänellä ole tätä merkkiä, joka on pedon nimi tai sen nimen luku.

18Tässä vaaditaan viisautta. Se, jolla on ymmärrystä, laskekoon pedon nimen lukuarvon: se on erään ihmisen luku, ja se luku on kuusisataakuusikymmentäkuusi.

Brittitutkija varoittaa Suomea venäläisistä

”Rosatomin ydinvoimalatyömaa Pyhäjoella mahdollistaa Venäjälle monenlaiset peiteoperaatiot Suomen kautta, brittitutkija Mark Galeotti varoitti IS:lle.” IS

Varoitus on erittäin aiheellinen. Suomessa on paljon niitä, jotka ovat olleet kaiken aikaa epäileviä yhteishankkeesta venäläisten kanssa.

Muistissa on vielä viime kesän tapahtumat Turun saaristossa, jossa venäläiset olivat pesiytyneet saaristoon vakoilun vuoksi.

Onko Suomen päättäjät hyväntahtoisia hölmöjä, kun eivät näe vaaroja venäläisten kanssa asioidessa vai onko kysymys korruptiosta. Entinen pääministeri Paavo Lipponen on ollut jo vuosia venäläisten konsultti, joka tarkoittaa, että venäläiset tietää tasan tarkkaan, miten Suomessa on toimittava.

https://www.is.fi/ulkomaat/art-2000006037478.html

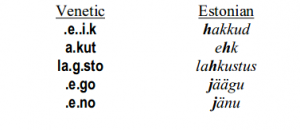

Veneetin ja itämerensuomen hämmästyttäviä yhtäläisyyksiä.

Veneetit olivat Rooman toiseksi tärkein kansa sen muodostuessa suurvallaksi II puunilaissodan aikana n. v. 200 e.a.a. (Hannibal vs. Fabius Cunctator). He ratkaisivat tuon sodan ensin olemalla liitty- mättä sen mm. kelttiläisten naapuriensa tapaan Karthagon armeijan ylipäällikön Hannibalin johtamiin vihollisiin, ja sitten liittoutumalla Rooman kanssa ”tasavertaisesti” ilman alistetun äänetön kumppani -”liittolaisen” vaihetta. Vaikka veneetit asuivat varsin lokoisia paikkoja viljelyn, karjanhoidon ja kalastuksen kannalta, heidän ratsuarmeijansa oli teräkunnossa, koska he olivat jatkuvasti harrastaneet vaarallista hevoskaravaanikauppaa pitkin Eurooppaa.

Tuossa vaiheessa Rooman kansalaisuudesta tehtiin tavoiteltu ”hyö- dyke”, ja samalla linjalla jatkettiin roomalaisten kunnioittamien kreik- kalaisten suuntaan. Roomalaiset eivät pitäneet veneettejä keltteinä, mutta he olivat huolissaan näiden kelttiläistymisestä. Sellaisen kat- sottiin pitkälle jo tapahtuneen – paitsi kielen osalta. Oliko kieli säilynyt omillaan – vai vaihtunut pitkälle latinaan, sitä tarina ei kerro.

Veneetit olivat sotavaunukansojen jälkeläisiä kuten latinalaiset ja kel- titkin. Kreikkalaista ja germaaneista ei niin ole varmaa. He olivat asut- taneet Aigeian meren pohjoisrantaa viimeitään edellisestä vuositu- hannen vaihteesta, ja käyneet siitä alkaen pronssi- ja meripihkakaup- paa aikaisempien asuinsijojensa suuntaan Baltiaan ja Tanskaan. Heidän kielessään on paljon sanoja kantaindoeuroopasta, jotka ovat muuntu- neet samalla tavalla kuin latinassakin. Mutta on paljon myös muuta sanastoa.

Jos edes jotkut heistä, vaikka vanhojen sotavaunujumalien (Reitia-jumalatar, mahdollisesti sotavaunukansan tammajumalatar Ratainitsha (eli ”Rattaiska”) papit, olisi puhunut suomalsiperäistä kieltä, se tarkoittaisi, että myös sotavaunukansaan oli osallistunut kielellisesti uralilaisiakin heimoja omana itsenään eikä vain Volgan vasarakirveskansan (Fatjanovon kulttuuri) kielessä ja geeneissä ”lisämausteena”. Tätä kandanvirolainen Angres Pääbo tulee väittäneeksi. Sotavaunukansa siis ei puhunut kantaindoeurooppaa, sellainen oli hajonnut jo ainakin tuhat vuotta aikaisemmin.

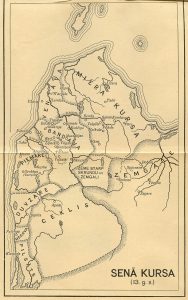

Veneettien tärkeitä vanhoja kaupunkeja olivat Tergeste (”Torille asti”, Trieste), (At)Este , Opiterge (”Ruokatori”, Oderzo), ja mahdollisesti etruskeilta vallattu Padua (Po-joen etruskinkielinen nimi, Padova, josta Rooman aikana tuli pääkaupunki). Venetsian kaupunki perus- tettiin vasta 400-luvulla balttilaiseen tapaan suoalueiden keskelle linnakkeeksi ja turvapaiksi hunneja vastaan. Latinalaistuneita asukkaita nimitettiin ilmeisimmin edelleen veneeteiksi.

Andres Pääbon tulokset eivät osoita varmuudella, että veneetti olisi koskaan ollut SU-kieli, sillä vastaavanlaisia yhtäläisyysluetteloja on joidenkin balttikieltenkin kuten kuurin kanssa. Mutta niiden kanssa on myös ratkaisevia eroja kuten nominien suvut ja verbien aspektit, liettuan tooni ja liikkuva paino jne. Pääbo väittää, että sellaisa ei ole ollut veneetin kanssa. Mutta verbisysteemiä, joka ratkaisee, ei huippuhyvin tunnetakaan.

Aukštaičių Ratainyčia

http://www.paabo.ca/papers/veneticgrammar+dots.pdf

” PART TWO: GRAMMARA DESCRIPTION OF VENETICGRAMMAR

Expanding the Discussion from “THE VENETIC LANGUAGE

An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL” (rev 6/2015)

Andres P ä ä b o (Ontario, Canada)

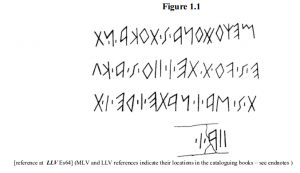

The following paper is from the chapter on Venetic Grammar docu- mented in “THE VENETIC LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL” in order to present a summary of the Venetic Grammar as discovered in the study – with some improve- ments and expansions from the original, wherever some further observations could be made. As explained in the above document, this grammar is basically achieved directly from the Venetic inscriptions. The methodology required first the discovery of word stems with the same meaning across all the inscriptions in the study which then produced grammarless sentences of the kind ‘Man –duck– elder’.Along he way,I keep an eye on the grammatical endings and manage to determine meanings as I go, but the final results for grammatical ending functions is only reached when arriving at the end. The methodology of deciphering involved a great deal of attention to the context as determined by archeology, in which the sentences must appear so that whatever meaning is assigned has to resonate with the context; and also context within the sentence.

Thus the methodology did not project any known language onto the Venetic. However,once it was clear Venetic was Finnic,I began to take notice of parallels in Estonian and Finnish and – discovered some ma- jor grammatical endings were close to the same. In languages, gram- mar changes most slowly, and that is why more distant languages will still be similar in grammatical features. And that is also why for any suggestion that Venetic was genetically connected to Estonian or Finnish, we MUST find similarity in grammar. The similarities were also noted since if Venetic was Finnic, Estonian and Finnish grammar can now be used for further insights. The following is intended for the average educated reader who has used common grammar descriptions. My work contains little linguistic jargon and this paper should be easy to read.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 The Most Comprehensive Description of Venetic

So Far Created Grammar cannot be directly discovered. It is neces- sary to include its discovery in the generalpursuitofword stems, and meaningful sentences that agree with the archeological context. It is only during the discovery of sentences and maintaining a constancy in word stems, that it is possible to look for the grammatical endings thatfunctionin the same way in all the sentences.

32

It is only inthe final stagethat the gaps in terms of grammatical mar- kets get filled inand we havean organized description. That is the reason I did not create this description of grammar until thevery end.

See “THE VENETIC LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL” for the word stems and translations of the exis- ting sentences on the archaeological objects. They say that the only way to prove that you have discovered a real language is if you have identified sufficient word stems (lexicon) and grammar that you can form new sentences that have not existed before. I have achieved this, as will be clear in some examples in this paper. However, there will be some critics who say that it is possible to invent a language and that I have invented all this. After all it is well known that some fantasy movies have hired linguists to create new languages for the movie (example ‘Klingon’). I agree that it would be easy to invent a language using some of the structures of existing languages. But it would be impossible to invent a language so that if applied to real ancient texts, it consistently produced translations that were sui- table for the context in which the sentences appeared, unless this invented language was the real language of the ancient texts. In the recent traditions of interpreting the Venetic inscriptions via Indo-European Latin or (more recently) Slovenian, the methodology has been to project the known language onto the unknown. Linguists participating do nothing other than try to vaguely ‘hear’ the known language in the unknown and then do some rationalizing to give it legitimacy. Not only is there a projecting of Indo-European word stems onto the Venetic inscriptions, but also desperate attempts to project Indo-European grammar onto the inscriptions.

In the Latin approach,there was nothing that actually could be inferred from the inscriptions themselves other than the “dative” suggested by a number of inscriptions associated with giving an offering to a deity. Otherwise there was mostly a projecting of Indo-European features onto the Venetic sentences (see Lejeune).

Recent Slovenian attempts to interpret Venetic did not even attempt to identify word stems and grammatical elements to build a lexicon and grammar, but obscured the problem by pretending the Venetic sentences were all very poetic and complex and generally similar to Slovenian. The following extensive rationalization of grammar from the inscriptions themselves, is completely new.

You will not find any rationalization even to a tenth the degree in any previous investigations. Our inventory of words from the Venetic inscriptions is not presented here, but we will make use of the min the illustrations and explain the words we use. The purpose of this paper is to discuss Venetic grammar and to show how Venetic grammar resonates with common Estonian and Finnish grammar. Anyone who claims Venetic is genetically related to a particular language family must be able to do this. Linguists have established that as languages from the same origins diverge from each other, grammar changes most slowly. Common grammar is in constant use. It is transferred generation to generation with little or no change. For that reason, when linguistics tries to find genetic connection between two languages whose common parent existed very long ago, many thousands of years ago, too distant for conventional comparative linguistic is applied to words, then a comparison of grammar is very revealing. For example, it is difficult to determine a genetic connection between Estonian and Basque purely from comparing words, but when one looks at the grammatical structures, the Estonian grammar and Basque grammar look very similar.

33

1.2 Proposed Theory of How Venetic could be a Finnic Language

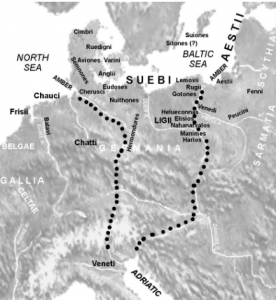

Finding in our investigation documented in “THE VENETIC LAN- GUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL” that the Venetic in the Adriatic Venetic inscriptions was a Finnic language, will inevitably raise questions as to how this can be the case. The fol- lowing is a brief account of my theory. Archeological finds in the last century has found that there were strong trade ties between the Jutland Peninsula and the north Italic region. In addition archeology has traced, from dropped amber, an amber route that began at the Elbe River and eventually came down the Adige River tothe center of the Venetic colonies at Este (ancient Ateste). Another amber trade route came south from the southeast Baltic amber source, went via the Vistula and Oder to the vicinity of Vienna and then south to the Adriatic Sea.It stands to reason that if there was a Finnic language at the sourced of amber, then if the northern traders with a monopoly on Baltic amber established trade routes and markets towards the Mediterranean, than they would have established these with their own people, hence would have established their northern Finnic language.

Archeology confirms, as I already mentioned, that there was an am- ber trade route from the Baltic to the Adriatic Sea. Ancient historical texts also confirm that the Adriatic Veneti were known for dealing in amber. This then is the connection between Venetic and the Finnic north. What was the character of the Finnic language in the north? All evidence suggests that the Finnic language was derived from the first hunter-gatherer peoples across northern Europe,who, because the north was flooded by the melt water of the Ice Age glaciers as they retreated to the mountains of Norway, were highly developed in living in a watery landscape and using dug out canoes. Archeology identifies this culture as the “maglelmose” culture. When later in history, the highlands of central Europe became settled with farming peoples, there was a growing demand for trade to connect the settled peoples to one another through trade. The obvious source for traders in a world with not other long distance transportation routes than river, were the aboriginals who were already travelling long distance in their annual rounds of hunting and fishing. The ori- ginal Finnic peoples of northern Europe became quite varied. In the remote north, they remained primitive well into historic times, but those who became involved as professional traders with southern Europe became quite advanced. My theory is that it is the advanced groups who took on the role of professional long distance traders for the sedentary civilizations, that produced the peoples ancient historical texts have called “Veneti”.

(The word, as VENEDE, is a genitive plural of VENE, meaning ‘boat’)

1.3 Limitations of Linguistics in Basic Interpretation of Unknown Language

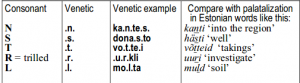

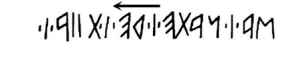

Scholars often have a false idea that the deciphering of an unknown language,is a task for linguistics.This is not true.Linguistics is the stu- dy of language, and that means it can only study known languages, since if a language is unknown it is nothing but meaningless sounds. Thus it is necessary to at least partially decipher the language before linguistic methodologies can be applied. In the tradition of deciphe- ring the Venetic inscriptions, linguists have been too quick in trying to apply linguistics–making observations and pronouncements before the language has been revealed. Since all languages have various patterns, it is possible for linguistics to identify 34 patterns and then completely misinterpret those patterns. A good example is a complex theory to explain the location of the dots in the Venetic writing, whereas in my study I found the dots were simply markers for palatalization and similar features that were probably not relevant linguistically (since when written in the Roman alphabet, the dots disappeared, and instead there were the normal Roman dots to separate words.) In addition, when Indo-European was forced on the inscriptions, what I found to be a case ending, was interpreted by linguists as female gender markers. The result was that linguists worked with rather arbitrary determinations, without the reever being any solid results in the basic interpreting of the sentences.

Most people assume that since we are dealing with language, then the matter of deciphering language is a linguistic one. But the fact is that if you give a linguist a recording of an unknown language, he or she will just hear meaningless noise. The most he or she can do is to identify the repeated patterns. But what do those patterns mean. You can only determine the meanings of those patterns by obser- ving it in actual use. In order to determine the meaning of a word like “Phikbith” he or she has to watch the word in action and infer its meanings, like any child does. Or use gestural language with a questioning look – for example point to a tree and say “Phikbith” with a questioning look and recieved a nod. While it is true that the linguist can propose that the unknown language is related to a known one and try to project the known one into the unknown, this is a specula- tive approach that can be wrong and great success is needed to prove it is true. The number of Venetic inscriptions is too limited for this approach to work. The tendency has been to make an assump- tion and then not let it go even if there is no real success. It is not difficult when the data is limited to use imagination to justify not letting the hypothesis go.For example even though the Venetic lan- guage has non-Indo-European Etruscan to the south and Ligurian to the east, nobody actually tested non-Indo-European. The tradition of analysis became obsessed with ancient Latin for no other reason than that most analysts knew Latin and could participate. We must understand how limited linguistics is if the language is unknown and if there is no‘informant’ to give translations in a known language. We must also recognize that simple proposing the unknown language is related to a known language is nothing more than a hypothesis to be tested, and that being the case, if there is not significant success, the option of the hypothesis being wrong must be recognized and the analysts must let it go.

On the other hand, when the language is deciphered from direct analysis of it in actual use, then all results will tend towards the truth because they are based on direct observation. For example, if you point to a tree, and the speaker says Pthigluk, then the probability is high that Pthigluk means ‘tree’. As you saw in my document of my methodology, even though Venetic is no longer spoken and that one cannot ask a speaker, the fact is that the Venetic language appears in short sentences on archeological objects that strongly suggest the nature of the sentences written on them. By cross-references across the body of objects, we can make very good guesses as to meanings of words, and then refine the meanings.

See “THE VENETIC LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL” for a detailed description of the ideal methodo- logy I used, and which eventually revealed the Venetic language was Finnic.

1.4 Basic Characteristics of Finnic Languages

Because in the end,we found that the Venetic language looked Finnic, I organized my description of Venetic in a form that makes reference to Finnic languages. Since most readers will know very little about Finnic language (the best known are Finnish and Esto- nian), here is a basic summary of characteristics of Finnic languages.

35

If Venetic is Finnic we will expect similar characteristics in Venetic and I will identify them.We will also structure our description of the Vene- tic grammar with similar grammatical terminology as is used with Fin- nish and Estonian today.The moment I claim that Venetic looks Finnic, I am obliqued to find that its grammar is similar to the grammar of Finnish and Estonian. Linguists say that basic grammar changes very slowly in langua- ges, and therefore if Venetic is Finnic, we MUST find Venetic to have basic similarity. If we fail to find the similarities that will then prove we are wrong, and that similarities in words are probably from borrowings. For example, in my deciphering of the inscriptions I found evidence of some words that seemed of Germanic origins, but since the grammatical structure was Finnic in nature, those Germanic words would have been borrowed. There would also be other borrowings too. It is only the grammar that reveals genetic descent. The following is an introduction to characteristics of Finnic languages which we will identify in Venetic.

MANY CASE ENDINGS/SUFFIXES, ADDED AGGLUTINATIVELY.

Venetic as a Finnic language would be agglutinative. That means case endings (or suffixes),can be added to case endings to express comp- lex thoughts. This is actually a degeneration of the most primitive forms of language which have a relatively small number of stems, and an abundance of suffixes, affixes and prefixes. Linguists call a language that is extremely of this nature ‘polysynthetic’ . The Inuit language is a good example. There are indications in some Inuit words and grammar that it has the same ancestor as Finnic languages. Finnic languages are best understood if they are seen as having such a ‘polysynthetic’ foundation, and then being influenced towards the form of language seen in Indo-European. (It is important to note that the modern descriptions of Finnic languages like Estonian and Finnish are some what contrived in that they modeled themselves after grammatical description models similar to what had already been done in other European languages. The reality is that Estonian or Finnish case endings are merely selections of the most common endings from a large array of possible suffixes. Thus even though in the following pages we are oriented to specific formalized case endings in Estonian and Finnish, there remains also suffixes that could have been case endings if the linguist who developed the popular grammatical descriptions had chosen to. The difference between ‘derivational suffixes’ and ‘case endings’ is merely in the latter being commonly applied in the opinion of the linguists who described the grammar.

PREPOSITIONS, PRE-MODIFIERS, CASE ENDINGS & SUFFIX MODIFIERS

It seems as if in the evolution of language, the ‘polysynthetic’ form degenerated in the direction of our familiar modern European lan- guages, where there are less and less case endings, and more and more independent modifiers located in front. Finnic languages are not as ‘primitive’ as Inuit, and have developed through millennia of being influenced from the languages of the farmers and civilizations – some premodifiers, adjectives, prepositions and otherfeatures placed in front. Venetic, like modern Finnic, present some instances of prepositions and pre-modifiers, like va.n.t.– and bo– but in general there are very few modifiers in front. It appears that instead of adjectives, Venetic liked to create compound words, where the first part – a pure stem without case endings – was somewhat adjectival.

36

NO GENDER. NO GENDER MARKERS ON NOUNS

There is no gender in Finnic languages. There is no ‘la’ or ‘le’ in front, nor any gender marker at the end. English too lacks gender in nouns, so that will not be a problem for English readers here. But there is only one pronoun in Finnic for ‘he, she, it’. In Venetic we do not mistakenedly consider some repeated ending to be a gender marker, but we always look for a case ending or suffix.

NO ARTICLES. USE PARTITIVE INSTEAD OF INDEFINITE ARTICLE

In English and many European Indo-European languages, there are definite and indefinite articles. For example French has un or une as the indefinite article and le or la as the definite article. Finnic does not have it. Instead the indefinite sense as in ‘a’ or ‘some’ is expressed via the Partitive. The Partitive is a case form that views something as being part of something larger. For example “a” house among many houses. or “some” houses among many houses.

PLURAL MARKED BY T, D or FOR PLURAL STEMS I, J

Plural in Estonian and Finnish is marked by T,D or I, J added to the stem according to phonetics requirements. Finnish only uses the Tin the No- minative and Accusative, and then uses I, or J to form the plural stem. Estonian uses T for plural stem, and then uses I or J if necessary where phonetics calls for it. Venetic appears to have both plural markers too, but perhaps more like Estonian. As we will see, there is more reason to attribute Estonian conventions than Finnish conventions to Venetic. (There is reason to believe that Estonian and Venetic / Suebic have the same ancestral language – see later.)

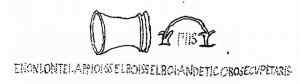

CONSONANT AND VOWEL HARMONY, GRADATION

Venetic shows evidence of consonant gradation and vowel and conso- nant harmony. For example if a suffix/ending is added to a stem with high vowels or soft consonants, the sound of the suffix may be altered to suit – with a lower vowel going higher, or a soft consonant going harder. For example ekupetaris has hard consonants P,T, hence the K in eku instead of G as in.e.g.e.s.t.s. We can find similar situations with vowels, unforunately the Venetic inscriptions are phonetic and capture dialectic variations, and the number of examples is very small.

COMPOUND WORDS – FIRST PART IS STEM, SECOND PART TAKES ENDINGS

A compound word occurs when a word stem is added to the front of an- other word stem. Thecase endings then are added to the combined word. We can detect them in Venetic when we see a naked word stem in front of another word stem but the latter taking the case endings.

WORD DEVELOPMENT

Generally all words develop in the following way, but this is less noticable in the major languages today. Words began with very short stems with broad, fluid, meanings.

37

As humans evolved, they needed to name things more specifically, and did so by combining them with additional elements – suffixes, infixes and prefixes. As the new word came into commonuse, the new word would become a stem in itself, taking its own grammatical endings. Because of abbreviation and other changes in the stem, the fact that the stem arose from a simpler stem, becomes obscured. For example in Estonian we might create the word puu-la-ne ‘tree-place-pertaining to’ as a poetic word for an animal who lives in trees. If this word were to come into common use, such as describing a squirrel, we might have puulane = ’squirrel’ which then over time might degenerate topulan. Puulane > pulanthen is a stem for endings, such as pulanest ‘from the squirrel’. This is invented for illustration, but a real example might be how the word vee might have developed into the word for ‘boat’ as follows: vee (‘water’) > vee-ne (‘pertaining to water’) > vee-ne-s (‘object pertaining to water’) > reducing to vene (‘boat’). (In our analysis of Venetic, we looked into the internal construction of words for additional insights into meaning.)

1.5 If Venetic is Finnic, it must be looked at in a different way Finnic languages are NON-Indo-European language, and therefore most readers of this will be entering foreign territory.

Most scholars know absolutely nothing about Finnic languages, and that is and has been an obstacle to proper investigation of the Venetic inscriptions. When Veneticis regarded as Latin-like, or generally Indo-European, then a million scholars can try to relate toit. But when Venetic is viewed as NON-Indo-European, the number of scholars both educated and interested in the subject drops to merely handfuls. That is the reason why it will be far easier for some scholars to reject this work outright, so as not to have to enter the foreign world of Finnic languages. Basically Finnic languages are strong in case endings, and case endings can be added to case endings. This is a very old manner of constructing sentences. The only more primitive language forms can be seen in either ancient Sumerian, or today’s Inuit of arctic North America – where ideas are formed by combining small syllabic elements. In the course of the evolution of languages case endings became incorporated into word stems, and the freedom to play with case endings decreased. Also modifiers became separate words placed at the front.There has been a steady conversion of human kind’s language from short syllabic words freely combined, to today’s large number of independent words. It can be compared to making soup from raw vegetables compared to buying ready-made soup in a can.

Modern words are the consequence of the ‘canning and cooking of basic elements’. In Estonian and Finnish it is possible to see the consituent elements in words. For example the word Eestlane, ‘Estonian’ or in Finnish Eestiläinen, is regarded as a word, but already adds two elements onto the stem Eesti. We have –la meaning ‘place of’ (Eesitla = ‘Estonian place’) and then –aneor –ainen meaning ‘pertaining to, of the character of’ These are not recognized as case endings because they are not freely added in actual usage, but poetic authors could do so. For example I already pointed out that using puu ‘tree’, one can say puulane and could use it to mean ‘animal of the tree’ such as a squirrel or monkey or even a human who lives in a treehouse. Today a large number of endings are not regarded as adding case endings but as ‘derivational suffixes’ I think part of the problem was that past Finnic linguists did not want to stray too far from the grammar descriptions of Indo-European languages. Thus, using the above examples, Eestlane or puulane are wordsin themselves and to this wecan add more case endings. We can thus have Eestlastele from Eestlane–t–ele ‘to the Estonians’.

38

But from a more polysynthetic view, we have Eesti-la-ne-t-ele. A great deal of the Estonian and Finnish words already contain many of the abovementioned ‘derivational suffixes’ which to a great extent can be case endings too if an author wants to play with them. It shows the progression – that as structures with case endings become used so often they seem like words in themselves, the constituent case endings become frozen into them. It is howall the words in all languages evolved. All that has happened is that some languages progressed slowly on this path, which other progressed slowly. From a Finnic perspective, some Venetic words produce revealing results when broken down into their elements. For example the goddess is addressed with $a.i.na te.i. re.i.tiia.i. 2 I interpreted $ a as the basic stem meaning ‘lord, god’ -.i.- is a pluralizer, and –nais a case ending meaning ‘in the form, nature, of’. The resulting meaning is to describe the goddess having ‘the character of gods’. It resonates a bit with Etruscan eisna ‘divine’ and with Estonian issa- ‘lord’ and we can form a parallelissa -i-na The intent was to address the goddess in the praiseful way so that the whole $a.i.na te.i. re.i.tiia.i. means ‘joining with You, Rhea, of the nature of the gods’ (‘of the nature of the gods’ can be stated simply with ‘divine’.) Words that were difficult to decipher from context, became easy when broken apart into Finnic-type elements, but often resulted in abstract ideas whose precise meaning needed some imagining of what went on in the actual context. For example V.i.rema.i.stna.i. (v.i.rema = v.i.-re-ma-and then v.i.rema-.i.-.s.t-na-.i.) which is very abstract but because it was used in place of $a.i.nait has to be praisful, and so I decided it meant something like ‘uniting with Rhea in the nature of arising from the land of life energy’. Similar sentences in the same context plus the context of the sentence, helped move towards the more precise meaning. Note that ancient language was always spoken in context, so that the context would help in making the meaning clearer. Thus in this section of describing the results of my determinations of case endings, you have to think in a different way than when thinking of Indo-European languages.

1.6 Some Notes on reading Venetic Writing

(For More Detail SeePart A) Venetic writing was peculiar in that dots were added between characters, whereas Etruscan and Latin used dots only to mark word boundaries. Analysts puzzled over these dots for a long time, and finally there was a complex theory. But to me, the dot use had to be very simple. If it had not been simple, then scribes would have followed the Etruscan convention of marking word boundaries. I hit on the idea that the dots were like phonetic markers added when speech is transcribed phonetically – marks for pauses, length, etc. – except that I found the dot was an all-purpose mark. If the writer sensed that his mouth was palatalizing or something similar, he threw in a dot on both sides of the alphabet character. Most often it was a plain palatalization, but it could also signify “S” being “SH” by writing the character for .s. Or “R” could become trilled with .r. The convention is to write the Venetic text in small case Roman, introducing the dots in thecorrect places. 2 The $ represents in my approach a long S as in ‘hiss’. The small case Roman letters represent the Venetic characters. The dots are as found in the original sentences, and in my results mostly are phonetic in intent andmostly represent palatalizations. For details about the Venetic writing see the appropriate section in THE VENETIC LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL

2. VENETIC CASE ENDINGS2.1CASE ENDINGS IN GENERAL

2.1.1. Static vs Dynamic Interpretations of Some Case Endings

When one first looks at Venetic the first thing one notices are endings of the form-a.i.or-o.i.or-e.i. Sometimes there is a double II in front, as in-iia.i. A good example isre.i.tiia.i. The context of the sentence, even when it was viewed from a Latin perspective from imagining dona.s.to was like Latin donato, is that it was like a Dative – an offering was being given ‘to’ the Goddess. This remains true when viewed in our new Finnic perspective – something is brought ‘to’ Rhea. But is it a Dative? I was fully prepared to grant that ending, (vowel) .i.a Dative label, but the more I studied it wherever it occurred it seemed to most of the time have a meaning analogous to how in modern religious sermons, the priest might say ‘to join God’ or ‘to unite with the holy’ and so on. I eventually found this idea of uniting with has to be correct because in the prayers written to the goddess Rhea at sanctuaries, written in conjunction with burnt offerings, one is not giving the offering to Rhea, but rather releasing the spirit which then joins or unites with Rhea up in the clouds. But what was this case ending if it was not Dative? What case ending would mean ‘uniting with’? But then I saw the ending from time to time in a context where it seemed to be like a regular Partitive. If a regular Partitive has a meaning ‘a thing’ or ‘some things’ and can be described as something ‘being part of’ a larger whole, then if it were viewed in a dynamic way, would that not mean ‘becoming part of, to unite with’? If this is the case, then we would have to discover Venetic having a static vs dynamic interpretation in other case endings.

But let us assume the Partitive has two forms – the normal static form and a dynamic form (‘becoming part of, uniting with, joining’) Over- looking similar endings for the Terminative -na.i. or used for the infinitive use of (vowel) .i., we can find the example .lemeto.i..u.r.kleiio.i. – [funerary urn-MLV-82, LLV-Es81] ‘Warm-feelings. To join the oracle’s eternity’ In this describing of Venetic grammar we will not explain the entire laborious process of establishing the word stems. That information is extensively discussed in the main documen t- “THE VENETIC LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL”. Here the first word, a plural of lemecan only be a static Partitive – ‘Some warm-feelings’, while the second expresses a dynamic Partitive conveying the sense of ‘towards’ in the sense of ‘joining’ (‘becoming part of’) an infinite destination, the infinite future with which the oracle deals with. One may wonder if the double I (-ii-) is an infix that makes it dynamic. (See later discussion of the –ii-)

41

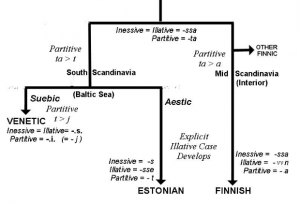

If it is possible for a language to allow a case ending to be interpreted in both a dynamic and a static way, what more can we say about it? What I mean by dynamic vs static meanings of a caseform? An example of dynamic vs static can be seen in how English uses ‘in’. One can say “He went in the house” and it would be clear the meaning is he went ‘into’ the house. And then I do un that Venetic appears to have both dynamic and static ways of interpreting ‘in’ as well. The Venetic Inessive (‘in’) is marked by .s. – often the meaning, as a result of context, ‘into’ not ‘in’ as Inessive requires. The only difference between the concept ‘in’ and the concept ‘into’ is whether there is movement. Thus one case can be used for both static and dynamic intepretations. The correct interpretation is determined from the context. Modern Finnic languages have developed explicit static vs dynamic interpretations – perhaps from the development of literature which promoted more precision. For example modern Finnic will have an explicit ‘in’ case in the Inessive and and explicit ‘into’ case in the Illative. But perhaps originally it was not that way. One indication of it is the fact that, for example, the Estonian and Finnish Inessive (‘in’) case endings are similar (Finn. -ssa versus Est. –s) and yet the Estonian and Finnish Illative (‘into’) case endings are different . This suggests that the Illative case is a more recent development and they do not have a common parent.

The common parent would have had an Inessive case that could have a dynamic meaning if the context required it. Then I think the use of the language – probably about a thousand years ago-putpressure on being more explicit and that lead to Finnish and Estonian developing an Illatie eachin their own separate way. Finnish has an Illative case (‘into’) that looks like it was developed out of the Genitive (‘of’) for example Finnish talo-Genitive talon, Illative taloon. Meanwhile Estonian has an Illative that looks like it was an enhancement fromthe originalInessive in that –s becomes –sse. Estonian (using talu) the Inessive (‘in’) talus, Illative (‘into’) talusse.

In summary, it appears that the ancestral language of Estonian and Finnish only had the Inessive, and that the Illative developed when Estonian and Finnish had branched away fromeach other, and perhaps onlyless than the last two millenia. In short, the Illatives being very different, are not related, while Inessives are similar, hence are related and must have been in the common ancestral language.

If Venetic only has the Inessive for both usages, then Venetic precedes any development of an explicit Illative. The development of the Illative described, indicate that they developed from a lengthening ofa static case. This lengtheingis a natural development when we wish to indicate movement. Forexample, Estonian Illative -sse can easily arise from the speaker of an original –ss implylengthening it to emphasize movement, as in talus > talusse. What is peculiar is that the Finnish Illative was developed by adding length to the Genitive! It is possible when you consider thatyou can start with a Genitive (talon ‘of the house´) and exaggerate it to get the concept of ‘becoming of’ (taloon ‘becoming of the house’ = ‘into the house’)

Thus, technically the Estonian Illative and Finnish Illative have different underlining meanings! This shows that if originally Finnic had static case endings that would assume dynamicmeanings (from movement) from context, the dynamic forms could be spontaneously implied bythe speaker simply lengthening it. We take any static case and add into the meaning ‘becoming’ as for example ‘into’ = ‘becoming in’. Thusif we accept that Venetic cases could be interpreted in both static and dynamicways, we have to allow all the static case endings the possibility of having dynamic meanings.

42

Returning to the Venetic Partitive. Depending on the context, the listener would interpret the Partitive ending either in a static way ‘part of a’ or a dynamic way ‘become part of a ’ideally interpreted in English as ‘unite with, join with’ . That is the reason, I interpret re.i.tiia.i. with ‘join with Rhea’ instead of simply ‘to Rhea’. I believe the intended meaning was that the item brought to the sanctuary and sent skyward as a burnt offering was intended to join Rhea, become part of Rhea – the Partitive case assuming a dynamic meaning here that had a more complex implication to it – that of the offering travelling into the sky and joining, uniting with, becoming part of Rhea. As I said above, the idea is reflected in modern religious ideas of ‘uniting with God’. We have above now identified two Venetic case endings that can be interpreted either statically or dynamically. (v means ‘vowel’) – v.s. can mean either ‘in’ or ‘becoming in’ = ’into’ -v.i. can mean either ‘a (part of)’ or ‘becoming part of’ = ‘join, unite with’ and an added –ii-may emphasize the latter. I notice that often the seeming dynamic interpretation of the Partitive in Venetic is preceeded with the double ii as in the example re.i.tiia.i. This insertion of the long ii sound may be an explicit development, analogous in the psychological effect of lengthening, to how Finnish achieves the Illative meaning by lengthening the last vowel (example taloon). It can therefore be interpreted with its psychological quality. The possibility exists that the double ii can serve as an explicit way of making the following ending dynamic. That is to say perhaps – iia.i. instead of just – a.i emphasizes the fact there is movement. We will consider the –ii-infix further later.

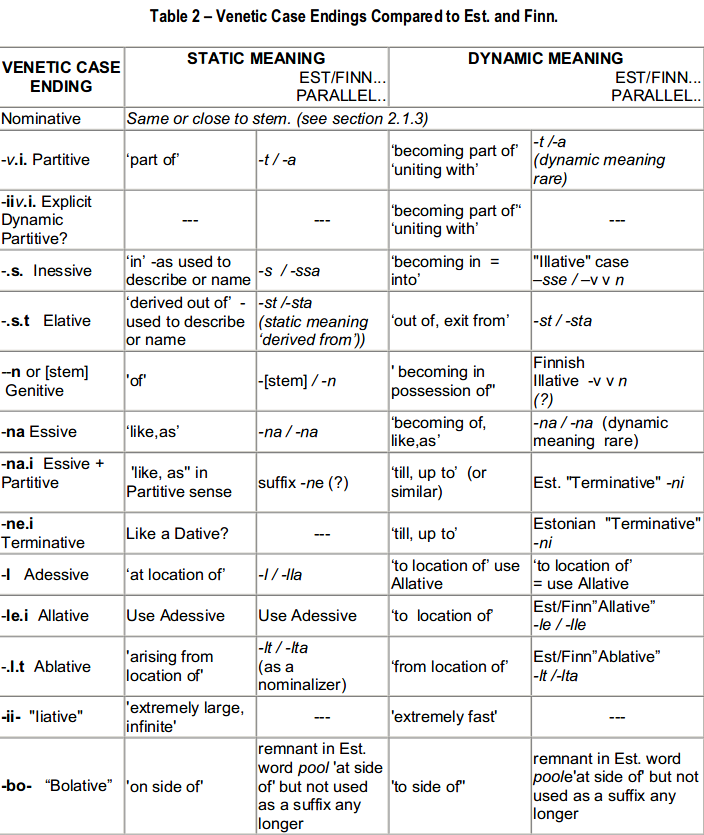

The following sections describe case endings, in the order of presence in the Venetic. The case endings names are inspired by Estonian case endingnames. We will reveal examples in theVenetic inscriptions and note them. However, case endings are really frequently used suffixes, and Venetic may have some additional suffixes which could be considered additional case endings for Venetic. A summary of our investigation of case endings and comparisons with Estonian and Finnish case endings will follow this section in the table at the end of section 22.

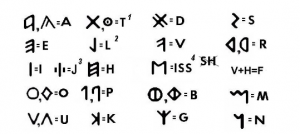

1.2. Introduction to Est. / Finn. Case Endings and the Presence of these Case Endings in Venetic.

Since we will structure our description of Venetic case endings in the standard descriptions used for Estonian and Finnish, and since we will make comparisons between Venetic and Estonian and Finnish case endings, we should first summarize the common case endings in Estonian and Finnish. The list is oriented to Estonian and the modern order in listing them. This is by way of summary of the ones we have looked at, showing which ones do and do not have resonances with Venetic. See also the chart given in Table 2. The following is an introductory overview of the possible case endings based on Estonian and Finnish. This will be followed by more detailed study of each, and how it is represented inVenetic. Nominative – identified by a finalizing element that has to be softened when made into astem. Even if the last letter may be hardened over the stem, there is no formal suffix or caseending. Genitive ‘of’ (Estonian) [stem], (Finnish) -n identified by a softened ending able to take case endings Venetic seems to have gone the direction of Estonian – ie Genitive given by stem

43

Partitive ‘part of’(Estonian) -t (Finnish) – a

Venetic appears to have evolved to convert the –tin the parental language of Estonian and Venetic/Suebic into –j(.i.) Inessive ‘in’ (Est.) -s (Finn.) –ssa Appears in Veneti as-.s., but Venetic uses it in both astatic way to describe something and a dynamic way with meaning of Illative ‘into’ Illative ‘into’ (Est.) –sse (Finn) –vvn NOT in Venetic, meaning the explicit Illative maybe a development since Venetic times, as I described above. Venetic allows –.s. to assume this dynamic meaning according to context needs.

Elative ‘out of’ (Est.) –st, (Finn) –sta strong in Finnic languages including Venetic but appearing mainly as a nominalizer and therefore must be very old Adessive ‘at (location)’ (Est.) -l (Finn.) -lla. Due to similarities between Est. and Finn. versions is another very old ending, hence expected within Venetic (and is as -l) Allative ‘to (location)’ (Est. and Finn.) -lle. Because it is found in both Est. and Finn. also very old, and we found it in Venetic as –le.i..

Ablative ‘from (location) (Est.) –lt (Finn.) –lta. Probably also in Veneticat least embedded in words like vo.l.tiio.

Translative ‘transform into’ (Est.) -ks (Finn.) -ksi Not identified yet in Venetic, but if it exists in both Estonian and Finnish one might expect it does exist in Venetic too. One watches for evidence.

Essive ‘as’ (same in all three languages) -na This is one of the endings that must be very old to appear in all three.

Terminative ‘up to, until’ (Est.) -ni (not acknowledged in Finnish grammar) This seems itmay exist in Venetic as Essive plus dynamic Partitive -na.i.–ne.i.

Abessive ‘without’ (Est.) -ta Not noticed in the Venetic, but could be there somewhere.

Comitative ‘with, along with’ (Est)-gaVenetic definitely presentedk’orkein themeaning ‘and,also’ as in Estonian ka,-ga. Unclear if it occurs as a suffix in Venetic. The following go through the above in more detail:

2.1.3. Nominative Case

In Estonian the nominative has a hard ending as it lacks case ending or suffix. If there is a case ending, there is a stem with a softened ending since more will be added to it. Common inEstonian is the softening of a consonant too.

For example Nom. kond, and stem becomes konna – Since we find in Venetic -gonta as well as-gonta.i. etc this character may not exist in Venetic. I expected in Venetic too the Nominative may show a harder or more final terminal sound than when it becomes a stem for endings. It may depend on the nature of the stem. But in the Venetic inscriptions I simply looked for the stem without endings and that would then be the nominative. It may seem strange, but the appearance of the Nominative in the Venetic inscriptions is very rare – almost always there was some kind of ending – because most of the sentences have the following as the subject (The nominative occurs only as the subject)

44

dona.s.to ‘the brought-thing’ dona.s.to however contains endings, as the primitive stem isdo- See discussion in section 1.2 Some other Nominatives (underlined)… ( Spaces added to show word boundaries)

5. K) .a.tta- ‘the end’ [urn-MLV-99, LLV Es2]

7. A) ada.ndona.s.tore.i.tiia.iv.i.etiana.o.tnia- [MLV-32 LLV-Es51]

Above we see the ending –ia Such an ending is indicative of the Nominative. It resembles the –ia ending used in Latin, but did not come from Latin since Venetic is older than Latin.

7. B) v.i.o.u.go.n.talemeto.r.na[.e.]b[.]| – “The collection of conveyances, as ingratiation producers, remains” [MLV-38bis, LLV-ES-58]

Above we see v.i.o.u.go.n.ta which is unusual since this word usually occurs with an endingand hence is not nominative – and ending like v.i.o.u.go.n.ta.i

In general, once you determine the word stem from scanning all words for the common firstportion, you can assume when that word stem occurs without any such ending, it is Nominative.Later we will see something similar when studying verbs. When a verb appears not to have anyendings, then we regard it as thecommonimperative. (See later section onverbs) For verbs wedetermine the verb stem by removingthe endings (The present indicative, past participle, infinite, imperative…)

2.1.4. Partitive Case -v.i. ‘part of; becoming part of’ This is the case ending that earlier analysis from Latin or Indo-European was thought to be “Dative” because by coincidence the mistakened idea thatdona.s.towas related to Latin donato, the prayers to the goddess seemed to speak of an offering being given to the goddess. (In realitynothing was being given directly to the goddess, but something was being burnt andits spirit wasbeing sent up to join with the goddess in the clouds, and that needed a different kind of caseending than simply giving.) Practically any static case ending could become a dynamic one which can be interpretedbroadly with ‘to’. A good example a Genetive ending meaning ‘of, possessing’’ in a dynamic sentence with movement can become ‘becoming possessed by’ as in ‘coming to be of, coming to possess’ which in a general way can be interpreted as ‘to’ in the sense that when something is given ‘to’ someone, it is becoming possessed by them. Similarly giving something ‘to’ someone can also mean ‘becoming part of’ (from Partitive) or ‘becoming inside’ (from Inessive, turning into an Illative meaning) or ‘coming to the location of’ (from Adessive, becoming Allative inmeaning).

As I said in 2.1.1, I believe that in actual real world use, the dynamic in-terpretation was dictated by context. But with the arrival of literature much context was lost and it wasnecessary to be more explicit in terms ofwhether a meaning was static or dynamic. And sometimes a meaning could shift.

45

I believe that Finnish Illative ‘into’ developed from its Genetive – that the dynamic Genetive meaning ‘becoming of, becoming possessed by’ came to be used in the sense of ‘becoming inside’. Similarly a dynamic Partitive ‘becoming part of, uniting with’ could shift its meaning towards the Dative idea of giving something ‘to’ someone. The main reason for my regardingthis case endingas a Partitive rather than another case thatwill also reduce to a Dative-like ‘to’, is that in some contextsin the inscriptionsit appears in aregular Partitive fashion much like in Estonian or Finnish. That means that the dynamic meaningof the ‘to’-concept actually means ‘becoming part of’, or ‘uniting with’, etc.

Comparing with Estonian Partitive.

Here is more evidence that this case ending in Veneticof the form -v.i. was intrinsically Partitive: we can demonstrate that the Venetic Partitive can beachieved if an Estonianlike Partitive (which may have existed a couple millenia ago in thecommon language) was spoken in an intensely palatalized manner. I explain it as follows: The Partitive in general can be viewed as a plural treated in a singular way (one item beingpart of many), and so the plural markers come into play.

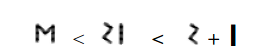

The plural markersin Finnic are –T-, –D-, and –I-, –J-; hence the replacement of T, D with J, I is already intrinsic to Finnic languages. When speakersof the ancestor to Venetic–Suebic–began to palatalize a great deal, they found the -J ending more comfortable than –T. Estonian marks the Partitive with a –T-, –D– and therefore it isn’t surprising that you can get a Venetic Partitive by replacing the –T-, –D-ending with –J-, as in talut > taluj (= “talu.i.”).

While it ispossible in this way to arrive at the Venetic Partitive ending from the Estonian one, one cannot do so from the Finnish Partitive. This suggests that both the Estonian and Venetic / Suebic languages had a common parent. Perhaps the Estonian Partitive came first. Then, with strong palatalization, the Venetic / Suebic Partitive, converted the –T-, –D-, to –J (.i.)

This and observations of the Inessive as well, give us a family tree of Finnic language descent which agrees with both archeological knowledge and common sense. I have shown it on the nextpage in a tree diagram. In it I show how we can arrive at the Estonian Partitive and modern Finnish Partitive from an ancient one, and then arrive at the Suebic/Venetic Partitive from highly palatalized speaking ofthe Estonian-like Finnic that was presumably the first language usedamong the sea-traders across the northern seas.Follow the Partitive in the chart. We begin with –TA which then loses the T in the descendants going towards Finnish, and loses the A in the descendants going towards Aestic and Suebic (as I call the two ancient dialects of the east and west Baltic Sea).

The common Baltic-Finnic language then on the west side interracts with “Corded-ware” Indo-European speaking farmers, and becomes a little degenerated and spoken with a tight mouth that results in intensified palatalization, rising vowels, and that the –T Partitive is softened to a frontal H or Jsound, which is what the Venetic Partitive ending -v.i. means.

Further Discussion: From an Estonian point of view, one can understand how there can be a dynamic interpretation because of the alternative Partitive and Illative in Estonian 3, where, using the stem talu, both the alternative Illative (a dynamic case meaning ‘into’) and alternative Partitive have the same form tal’lu based on lengthening. This suggests that the language from which this alternative form came must have had a dynamic Partitive interpretation like we see in Venetic, and its usage was so much like a newly created Illative that it was linked to the Illative.In thatcase the so-called Estonian alternative Illative is not an Illative at all, but a dynamic interpretation of the Partitive. Sometimes the only indication of the alternative Partitive in Estonian is emphasis or length. But this only underscores the fact that explicit dynamic case endings can easily shift their meaning

.One of the sentences discussed in THE VENETIC LANGUAGE An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL was.. (a).e..i.k.go.l.tano.s.dotolo.u.dera.i.kane.i- [container-MLV-242, LLV-Ca4] Here we see dera.i.kane.i ‘a whole container’ in the static Partitive interpretation. In Estonian the normal Partitive is to use –T-, –D– instead of the J (.i.) as in Est. tervet kannut but it is also common to say in Estonian terv’e kann’u adding length. Considering that Estonian was converged from various east Baltic dialects, in my opinion this alternative Partitive form in Estonian comes from ancient Suebic (the parent of Venetic) from the significant immigration from the west Baltic to the east during the first centuries AD when there were major refugee movements caused by the Gothic military campaigns up into the Jutland Peninsula and southern Sweden. The Suebic grammatical forms needed to converge with the indigenous Aestic grammatical forms, and so an original tervej kannuj (for example) evolved among these speakers into terv’e kann’u instead of reverting to the indigenous tervet kannut (which would sound unusual to people used to tervej kannuj)The following sentence below shows the general form used in regards to an offering being made to Rhea. It shows the most frequent context in which the dynamic interpretation is desired. (b)mego dona.s.to vo.l.tiiomno.s. iiuva.n.t.s .a.riiun.s.$a.i.nate.i.re.i.tiia.i. – [bronze sheet MLV-10LLV-Es25] Our brought-item ((ie offering), skyward-going, in the infinite direction, into the airy-realm[?], to (= unite with) you of the Gods, to (= unite with) Rhea When you think about it, the idea of uniting with or joining with a deity, or eternity, is more involving than merely moving to that location or giving something to it – which is the reason in religion today, it is more satisfying to ‘unite with God’ . In the case of the Venetic context it is the spirit, rising to the clouds via the smoke of burning, that unites with the deity. 3 Estonian has preserved alternative Illatives and Partitives that look similar or the same. Lengthening the next to last syllable as in talu > tal’luis a grammatical form that can be used either as a Partitive (normally talut) and as an Illative (normally talusse). Since this phenomenon does not exist in Finnish, it may have come from the south and west Baltic dialect spoken by the “Suebi” of Roman times, carried to the east Baltic by refugees from the Gothic military expansions of the early centuries AD. Suebic in turn can be linked via the amber trade to Venetic.

48

2.1.6. Inessive Case -v.s. ‘in; into’ (In dynamic meaning equivalent to Illative).

Static interpretation (‘in’): In today’s Finnic, the Inessive and Illative cases are considered different, but as we decribed in 2.1.1 above, it seems originally, in the parent language of Finnish, Estonian, ancient Suebic (from which the inscriptions Venetic came) there was only the Inessive, interpreted in both a static and dynamic way. And then in recent millenia, it became necessary to explicitly distinguish between the two. But Venetic, remaining an ancient language does not show this distinguishing, and for Venetic we determine whether it is the static ‘in’ or dynamic ‘into’ from the context. Was the action simply happening, or was the action being doneto wards something else? Was something merely‘being’, or‘acting on something’? An object that simply was, and did nothing onto anything else, would take thestaticmeaning. I already mentioned how in modern English, we can useinand the context could suggest it means ‘into’. For example “He went in the water” is technically incorrect, but from the context the listener knows the intent is “He went into the water”. This shows how easily the correct idea is understood from context, and why in early language it wasn’t necessary to have two different case endings. Also, in early language, all speaking was done in the context of things going on around the speakers and listerners. If language became separated from being used in real contexts – such as when it was used in storytelling or song even before written literature – it became more important to explicitly indicate the required meaning. There was another usage forthe staticform – as a namer. Many Estonian names of objectsend in –s seeming to be a nominalizer.

49

2.1.7. Elative Case -v.s.t ‘arising from; out of’

I include this next because we have already above discussed how –ste can be used to name some- thing. It is actually not so common in the body of inscriptions. Static Interpretation (‘arising from’) This is similar to the Inessive, in that the static form seems to have most often served the role of naming. Today Estonian and Finnish tend to view the Elative case in a dynamic way – something is physically coming out of after being in something. Thus as the table of case endings (Table 2 at the end of these case ending discussions) shows, it is the static form that is less known and less used today, which logically comes from the idea of something being derived from or arising from something else. This static form is the one that names things. As mentioned under the Inessive, where the static form also names things, a town with a bridge silla – could acquire a name two ways – with the static Inessive as a description Sillase, and with the static Elative with Sillaste.

Just as we referred to A tesisf or our example with the Inessive, there was also the town, Ateste at the end of the amber route. In this case the meaning is ‘derived from, arising from, the terminus (of the trade route)’. Another major Venetic city was Tergeste, which suggests‘arising from the market (terg) ’Interestingly the market at the top of the amber route, in historic times called Truso was probably in Roman times called Turuse (or Turgese or Tergese) in that case using the static Inessive manner of naming.)

Of course, as mentioned under the Inessive, it was not just used for place names, but to derive a name for something related to something else. I gave the example earlier of vee > veene > veenes which could refer to a boat and eventually reduce to vene. We could also have veenest but it would name something arising from water (like maybe a fishing net?) The difference between naming with –s(e) and naming with –st(e) is whether the item named is integrated with the stem item, or arising out of the stem item and separate from it. In the Venetic sentences, there are nouns that were originally developed from this static Elative ending. For example .e.g.e.s.t- is one. .e.g.e.s.t- could be interpreted as ‘something arising from the continuing’ = ‘forever’. The common dona.s.to could be interpreted as ‘something arising from bringing (do- or Est. / Finn too/tuo)’ Another is la.g.s.to which Iinterpreted as ‘gift’ but internally means ‘something arising from kindness’. (The reader should review my interpretations of the –ST words in the lexicon from this perspective – the stem word plus the concept of ‘arising from’.) Dynamic Interpretation (‘out of’)This is the common modern usage in Estonian and Finnish and this is the meaning we will find in their grammar describing case endings. The dynamic interpretation of the Elative in the body of Venetic inscriptions depends on our determining there is movement involved. The static meaning ‘arising from’ is abstract and there is no movementm but the dynamic meaning ‘(moving) out of’ involves movement.

51

2.1.9. Essive -na ‘as, in the form of’; ‘becoming as. ’

This ending is almost as common in the body of inscriptions as the Partitive and Inessive. We will assume for the sake of argument that this case ending too had both a static interpretation and a dynamic one, depending on context. I propose this was the case for all the Venetic case endings; but some case endings were more-dramatic in the difference between the static interpretation versus dynamic-for example case endings about location interpretation versus dynamic – for example case endings about location.

52

Here were are speaking of form, appearance and the differentiation between static and dynamic meanings is not significant in this case as it is a more abstract concept, and abstract concepts are quite static by nature compared to concepts involving actual physical movement or lack of movement.

Static Essive: In the static interpretation this ending has the meaning ‘as, in the form of, inthe guise of’ For example it appears in $a.i.nate.i.where$a.i.nais seen as ‘in the form ofthegods’ It appears more commonly in the inscriptions with an additional Partitive attached, giving -na.i This added Partitive usually results in a very dynamic meaning, which appears to be like Estonian Terminative ‘till….’

2.1.11. Adessive -l ‘at (location of)’ & Allative -le.i. ‘towards (location of)’

The Adessive in the meaning ‘at (location of)’ represents the static interpretation. In this case it seems Veneticdoeshave anexplicitdynamic form which parallels what is in relation to Estonian and Finnish called the Allative ‘towards (location of)’.

53

2.1.12. Ablative -.l.t ‘out of (location of)’

The Ablative also exists in both Estonian and Finnish in a similar way and therefore must exist in Venetic from its origins in the northern Suebic. The Ablative (-.l.t) to Adessive (-l) and Allative (-le.i.), is similar to the Elative (-.s.t) in relationto the Inessive / Illative (-.s.). The difference is that one deals with physical location, while the other (-.s.t) deals with interiors. Static Interpretation of the Ablative (‘derived from location of”) Similarly to the Elative (.s.t) the Ablative (-.l.t) probably was mostly used to create nouns, to name things, but inthis case related to a location – on top of it, not inside it. An example in Venetic is the word vo.l.tiio Could it have originated with AVA ‘openspace’? AVALT would then mean‘derived from the location of the open space’ This seems to accord with the apparent meaning ofvo.l.tiioas‘sky, heavens’.

54

2.1.13. Other Possible Case Endings, Suffixes Suggested from Estonian Derivational Suffixes

The above listing of Venetic case endings has com- pared Venetic case endings to Estonian / Finnish as summarized in 2.1.2. This comparison is absolutely necessary becauselinguisics has found that grammar changes very slowly and that if Venetic is really Finnic, thenwhat we found in the interpreting of Venetic from first principle, MUST show significant similarities to modern Finnic languages that were at the top of the amber routes to the AdriaticVeneti. Even though Estonian and Finnish is over 2000 years in the future or Venetic, the similarities must be demonstrable. But this idea of grammar having longevity is really part ofthe basic idea that commonly used language tends to endure. The common everyday languagetends to endure because it is in constant use. That means not only is basic grammar preserved from generation to generation, but also everyday words. Linguists have always known that some words – words relating to family relationships, for example – have great longevity. I have pointed out how the Venetic word .e.go and stem.e. is practically identical to Estonian jäägu and stem jää- and how this is understandable considering that even today the jää-stem is used all day. On the other hand, the Venetic word rako for ‘duck’ has no survival in Estonian or Finnish ‘duck’ is part and anka respectively. But how often is the word ‘duck’ used. Unless you keep a flock of ducks, only a few times a year. When a concept is rarely mentioned, alternative words can be used, at the whim of the speakers.. For example ‘duck’ could be expressed by a word meaning ‘water-bird’ or ‘wide-bill’. (Venetic rakosounds like it came from the quacking sound, and Finnis hanka, sounds like it actually originated with geese that go “honk!” The origin of the Estonian part is a mystery) So unless one word is used often the word lacks stability. But the same applies to grammar. The most common grammar – the grammar taught to babies – has greatest longevity. Thus we will find similarities to the most common grammatical features, andless so in rarely used grammatical features. The point is that longevity is proportional to usage, and therefore if someone compares a modern language with an ancient genetically related one, the correctness is more probable if the comparison is with very common words or grammar, and it helps if you learned the modernlanguage as a child, as then you will have an intuition about the core language. Such wisdom isnot available for those analysts who simply look up words in a dictionary, because in adictionary a very rarely used word can be beside a commonly used one. There is no filter. Although in this description of Venetic grammar follows the modern model for describing Estonian and Finnish, there can be other ways of constructing the descriptive model. As I have

55already mentioned, in reality in Finnic,the concept of case endings is artitificial–selecting themost common of a large spectrum of endings. The original primitive language might have beenvery much like modern Inuit of arctic North America. Linguists have not handled Inuktitut according to common ways of describing grammar, and they called it ‘polysynthetic’ (a system where the speaker simply combines short stems with many suffixes, infixes, and prefixes). The modern manner of describing Estonian and Finnish, is really a selection by linguists developing a description, ofthe most common, most universally used, suffixes. But there aremore. What they chose was to a large degree influenced by how grammar had been described inthe most common Indo-European languages. This means that there are other suffixes that couldhave been included with the stated “case endings”. But these further suffixes are in modernEstonian and Finnish, generally not identified in the grammar but rather incorporated into the common word stems in which they appear and so the suffix portions are not identified. There are many such suffixes that are common enough that a creative speaker could combinethem and in effect revivesome amount ofthe original polysynthetic approach of speaking. Many words with the suffixes built into them, are so common and so old, that speakers of Estonian or Finnish no longer think of how they were derived.

For example the word kond, ‘community’ is one an Estonian would not even think about in terms of its internal components. But when you think of it, it is in fact a combination of KO plus the suffix –ND, and the intrinsic meaning is ‘together’ + ‘something defined from’. Thus what we have is not only recognizable suffixes including “case endings”, but suffixes that have frozen onto the stem and assumed aquite particular meaning. In Venetic there some we have mentioned where the endings are incorporated into a new word stem (.e.ge.s.t, vo.l.tiio, etc, etc ) With Venetic too, there is a constant issue as to whether an apparent case ending is stuck onto a stem, or whether a new word has been established, which of course can add case endings itself. I believe that in the evolution of language, the polysynthetic constructions that were constantly used, became solidified from constant use. And then with people using it often, fromlaziness, it becomes contracted. Once contracted, the original construction is no longer apparent. Starting with mere tens of basic syllabic elements, evertually we end up with thousands of new stems that cannot be taken apart. The longer the language has followed this experience, the more new word stems arise, and thegrammatical elements become fewer and fewer. If we wish to use modern Estonian or Finnish to detect further case endings in Venetic, wecan reverse the evolution of Estonian or Finnish by noting still-detectable suffixes within words,and then see if Venetic has repeated use of one of them. So what kinds of suffixes are still apparent in modern Estonian or Finnish that are stillidentifiable as suffixes and not disappeared into new words stems?Today these suffixes are called ‘Derivational Suffixes’. Poets are free to create new words with them, but they are not recognized as case endings as they are not in regular use. But as we go back in time, it is likelysome of them were more commonly applied and if linguists had described Estonian or Finnish a few thousand years ago, they would have claimed more case ending. (The Finno-Ugriclanguage of Hungarian is an example of a language in an older state, and so linguists haveclaimed many more case endings.). There are about 50 suffixes enumerated in A Grammatical Survey of the Estonian Language by Johannes Aavik, most readily found within Estonian-English Dictionary complied by Paul F. Saagpakk, 1982 .It was and is important for us to be aware of these suffixes when looking at Venetic, to find resonances, since the ‘case endings’ definitions arbitrarily selected by linguists, may have excluded important suffixes that appear in Venetic.

56

For our purposes in deciphering Venetic, there was nothing to be gained by looking at morethan a few Estonian derivationalsuffixes in the listgiven by Aavik – those that we found worthyof consideration in our analysis ofthe Venetic. They also allow us to look at the internal makeupof a word, to determine in a general or abstract sense how the word originated, to assist innarrowing down its meaning. The following is a limited list of the Estonian derivational suffixes that I considered inanalyzing the Venetic. Some were very significant. -ma (= Venetic –ma?)Estonian 1st infinitive, is believed to have originated in Estonian as a verbal noun in the Illative. Something of this nature seems to be found in Veneticsuch as inv.i.rema. I believe it meant something like ‘in the state of v.i.re’-m (=Veneti –m?) where this appears inEstonian words it appears to have a reflective sense. It is psychological. It is a nominalizer too that may also produce the idea of ‘state of’ as in –maabove. Possibly it appears in the donom of Lagole inscriptionswhich obviously from how itis used means ‘something brought’, and a synonym for dona.s.to-ja suffix of agency, equivalent to English ending –eras inbuyer. I did not find anything solid in Venetic in this regard, perhaps because Venetic is likely to write it -.i.i and how wouldone distinguish it from all the other uses of “I” within Venetic! I believe that Venetic turned in another direction to express the idea of agency –o.r. see next. Estonian has it in the derivational suffic –ur so it is not entirely foreign. The way languages from the same origins evolve is that there may be two words or endings that mean the same, and one branch popularizes one and the other branch popularizes the other. Thus we can conclude that -ja maight have been found in Venetic, but that –o.r. was preferred. Nonetheless, the ending –ur is still recognized within Estonian. -ur (= Venetic -o.r.) indicating a person or thing which has a permanent activity orprofession, equivalent to English –or as in surveyor. Would appear in Venetic as –or. I foundthis onevery useful as it perfectly explained a word likelemetornaassociated with a stylus left as an offering ‘as a producer of warm-feelings’ – ie the object continues to be an expression fromthe giver after it is left behind. An example: v.i.o.u.go.n.ta lemeto.r.na .e.b.- [stylus-MLV-38 bis, LLV-ES-58] ‘The collection-of-bringings, as ingratiation-producers, remains ’Note how lemeto.r.na is composed of plural plus two suffixes leme-t-o.r.-na

57

Median rooli vaalikamppailussa

Helsingin Sanomat johtaa nyt koko valtamedian kampanjaa, jonka tarkoituksena on manipuloida, jopa aivopestä suomalaiset äänestämään ”oikein”. Samaan tapaan, kuin silloin, kun kansanäänestyksellä Suomi liitettiin EU:hun. Silloinkin Hesari johti kampanjaa EU:n puolesta.

Antti Rinne on nyt median suosikki pääministeriksi ja syykin on selvä. Rinne noudattaa Paavo Lipposen aloittamaa politiikkaa hallituksessa, joka on äärioikeistolaista ja hyvin EU-myönteistä. Se ei tiedä hyvää Suomen kansalle. Muistettakoon miten Lipponen pääministerinä kuritti köyhiä ja lapsiperheitä sekä vanhuksia ja suosi rikkaita. Demarien kaikki lupaukset ovat vain vaalitäkyjä, jotka unohdetaan heti vaalin jälkeen. Haittamaahanmuutto tulee jatkumaan ja jopa lisääntymään, jos Antti Rinne on päämisterinä.

Tänään uutisoitiin, että Jorma Ollila on nimitetty Alma-median hallituksen puheenjohtajaksi. Alma-median päälehdet ovat Iltasanomat, Talouselämä ja Kauppalehti, Satakunnan Kansa, Uusi Suomi ja Aamulehti sekä joukko eri alojen erikoislehtiä.

Jorma Ollila on Suomen yykkös bilderbergiläinen, joka oli salaseuran ohjausryhmän jäsen. Hän mm. valitsi ne suomalaiset, jotka valittiin ja kelpuutettiin salaseuran jäseniksi.

Kun tähän vielä lisätään Yle, niin meillä on nyt Suomessa tilanne, että koko media ottaa ohjeet ja journalistisen linjansa Illuminatilta eli Bilderber-salaseuran huipulta. Tämä ei tiedä hyvää ja enteilee, että ”uusi maailmanjärjestys ” on nyt toteutumassa pitkän esivalmistelun jälkeen. Siksi tarvitaan nyt mediaa, joka manipuloi ja aivopesee kansalaisia hyväksymään suuret muutokset, kuten liittovaltion muodostamisen.

Edellä esitetyt merkit tulevasta ovat niin selvät, että nyt pitäisi jo jokaisen tajuta, että meitä viedään nyt, kuin pässiä narussa.

Katso video se kertoo lisää. Suomenkielinen textitys.

Miten käy Suomen vaalien jälkeen?

Se on tietysti asia, josta ei pitäisi vielä puhua, mutta kun kiivaasti puhutaan,niin puhutaan sitten. Vaalien jälkeen muodostetaan hallitus, mutta miten pitkään siihen menee. Jos ennusteet pitävät paikkansa, niin demarit on suuri menestyjä ja sen mukaisesti pitäisi Rinteestä tulla uuden hallituksen muodostaja. Rinne on ihan mukava mies katsella televisiossa, mutta onko hän nykyään liian rauhallinen ja hidas pääministeriksi. Jättikö viimeaikainen sairaus kuitenkin jälkensä ja onko hänellä enää ”särmää” pääministerin tehtäviin, no se ei ole minun tehtäväni päättää siitä.

Nykyään tuntuu siltä, että hallituksen muodostaminen Euroopassa on äärimmäisen vaikeata. Se varmaan johtuu uuden maailman puoluekenttien jakaumasta, en halua sanoa, mutta paljon puhutaan populismista. Se on nykyään muotia, vaiko oikeata todellisuutta, en osaa siihenkään vastata.

Hallituksen muodostaminen kesti Ruotsissa monta kuukautta, siltä kuulostaa myös Virossa. Ei ollut helppoa Italiassa, ei Ranskassa ja vaikeata tuntuu olevan Englannissa. Englannissa on hiukan eri asia, mutta lujaa tahtoa sielläkin vaaditaan.

Aika näyttää miten meidän käy.

Näitä huippuällipäitä tulee mm. Iranista, Aganistanista ja Israelista

Mikä lienee syy; ihmiset siivilöityjä valtavasta ihmismassasta aikojen kuluessa vai ei. Juutalaiset on jo todistettu, mutta tämä ikivanha Persia ympäristöineen kantaa ilmeisesti jonkinlaista erityistä ällikulttuuria tai sitten, siellä erittäin vaikeista sotaisista olosuhteista selviytyjät ovat näitä jälkeläisiä- ällipäitä.

Kyllähän näiden ikivanhojen kulttuurien aikaansaannokset näkyvät vielä tuhansia vuosia jälkeen päin. Mesopotania, Rooma, Egypti, Kreikka, Kiina, Intia, jolloin Suomi oli jään alla tai metsää ja vettä. Mistäs me suomalaiset sitten olemme ”matkustaneet” aikojen kuluessa ?

Jotain hyvää tästäkin pitää nähdä- Suomessa.

Onko historiasta löydetty uusi suomalais-ugrilainen kieli?

Kyseessä olisivat muinaiset veneetit. Näin väittää kanadanvirolainen Anders Pääbo, joka on tutkinut ennen ajanlaskun alkua Adrianmeren rannalla ja myös Baltian rannikolla asuneiden tuon nimisten kansojen perintönä jääneitä roomalaisia tekstejä ja paikannimistöä ja lainosanoja molemmilla alueilla.

Italian kansat rautakaudella. Huom! Latinalaisten aika vaatimaton siivu faliskien ja umbri(alaist)en välissä. Lisäksi Rooma ei tuolloin kuulunut heidän ydinalueeseensa, vaan se oli (ensimmäinen?) heidän perustamansa colonia pohjoisesta etelään joh- tavien (hevos)karavaanikauppateiden ja rannikolta sisämaahan Tiber-jokea johta- vien merikauppareittien risteyksessä. Rooma kappasi kuitenkin muiden heimojen avulla vallan emämaaltaan ja tasavaltalaisen Rooman valtion valtiomuoto luotiin luotiin näiden heimojen hallintokompromissin tuloksena. Latium tarkoittaa tasaista, latteaa maata erotukseksi vuoristosta. Pääkaupunki oli ensin samaa tarkoittava Lavinium.

Kaikki harmaan sävyillä merkityt kansat ovat latinalaisten läheisiä kielisukulaisia. Saappaanvarren alueet muodostavat heimoliiton. Rooman, hyvän asiakkaan (?) pussiin pelasivat aina myös sicelit ja veneetit. Kun joku ulkopuolinen yritti niitä Roomaa vastaan usuttaa, kuten esimerkiksi Hannibal molempia, seurauksena oli juonittelijalle katastrofaalinen operaatio.

Latinalaiset tunsivat tarut Troijan sodasta ja väittivät kuninkaansa Aeneiaan osallistuneen siihen (Troijan puolella, ei siis Kreikan). Nimi Rooma tulee kantaindo- euroopan ”(ylä)virtaa” (ja erityisesti paikka jossa ylävirran kosket muuttuvat rauhalliseski joeksi) tarkoittavasta sanasta ”*s-rem-”, josta tulee mm. – yllätys – suomen Rauma, liettuan sraumė̃ , latvian straume = hidas virta, srūti (srū̃va, srùvo), vanh. *s-remti > *srauti (srauna, srovė).